|

Saint Méloir-des-Bois. "Field of Couavra woods"

"Rerum Cognoscere Causas" "Pour connaître la cause des choses" No. 168 Squadron RAF Fenrik. Jan Gert von Tangen See his biography |

|

Saint Méloir-des-Bois village as it was ( photo)

Sunday October 31st 1943 Saint Méloir-des-Bois. Field of Couavra woods

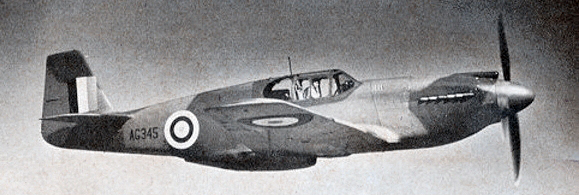

Aircrash of Mustang Mk.Ia FD554 piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Jan Gert von Tangen (Fenrick rank in the Norwegian Royal Air Force). A Norwegian reserve volunteer pilot with the Royal Air Force, and a member of 168 Squadron from the 2nd TAC ( Tactical Air Force); this young pilot had joined the squadron on August 25th 1943 coming from Old Sarum base in Wiltshire near Salisbury. Training flying school for tactical reconnaissance from 41 OUT (Operation Training Unit). The RAF 168 Squadron had been created in Snailwell near Cambridge, England on June 15th 1942. In June 1943 it rejoined Odiham base in Hampshire where it was equipped with Mustang Mk.Ia (P-51 Mustang, an American fighter plane designed by North American Aviation) and it became operational for photographic reconnaissance missions and anti-raid missions over enemy territory. The pilots from this unit came from the British Commonwealth, occupied countries from which these young men had fled from at the beginning of the war as well as from countries fighting against the Axis forces. They were eager to fight for Freedom and continued to enlist throughout the war. This youthfulness was also expressed a dream for adventure. More often than not their illusions were brought to naught by the hardship involved in warfare ; and unfortunately so were the lives of a great number of them.

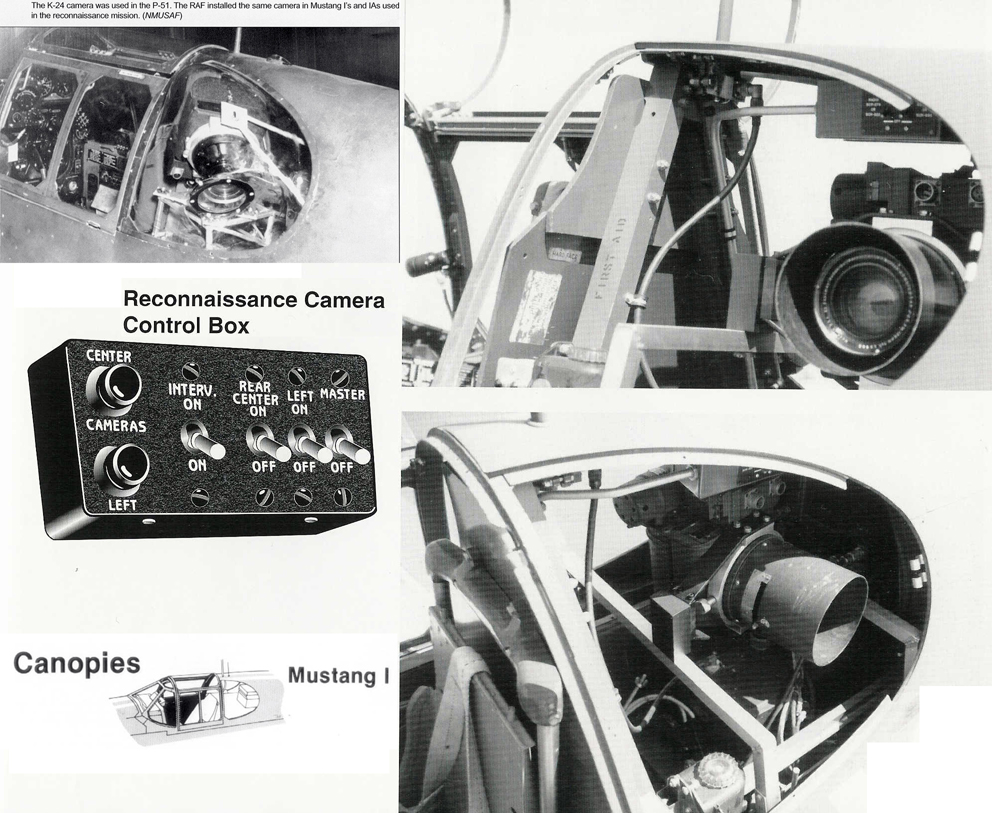

The Mustang I was a fighter aircraft manufactured in the USA by North American Aviation (its factories were located in Los Angeles, California and Dallas, Texas); it was acquired by the British through leasing. 618 aeroplanes (including 93 Mustangs) being released and allocated to numbers 2, 63,170,268, 516 and 168 Squadrons. This single engine fighter was equipped with a side-photographic device (one or 2 K24 cameras), that was fixed behind the pilot’s headrest; when activated it could provide five very high definition snapshots of strategic targets spotted during a flight or defined as main targets.

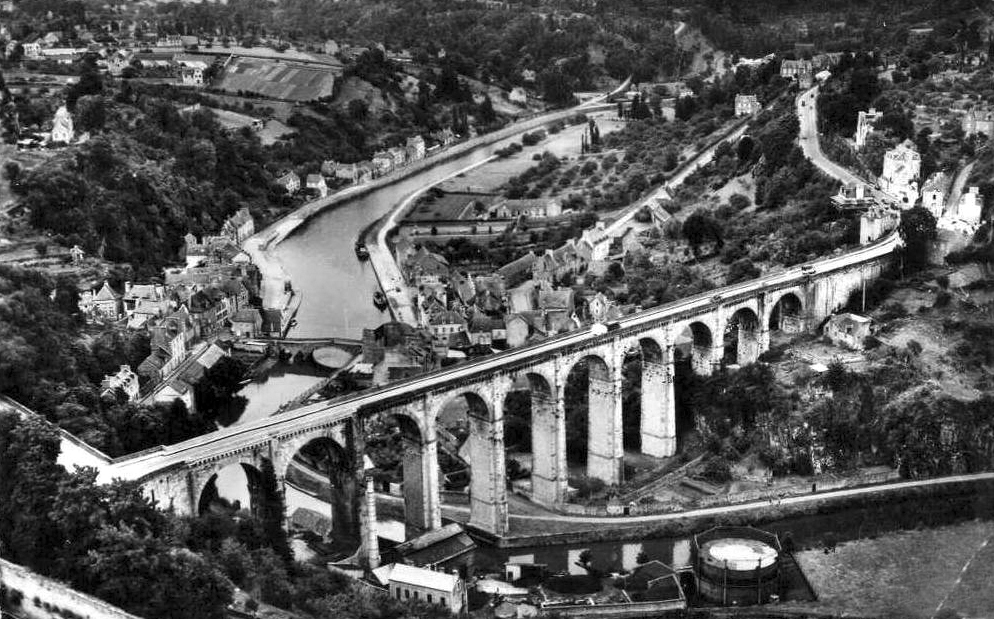

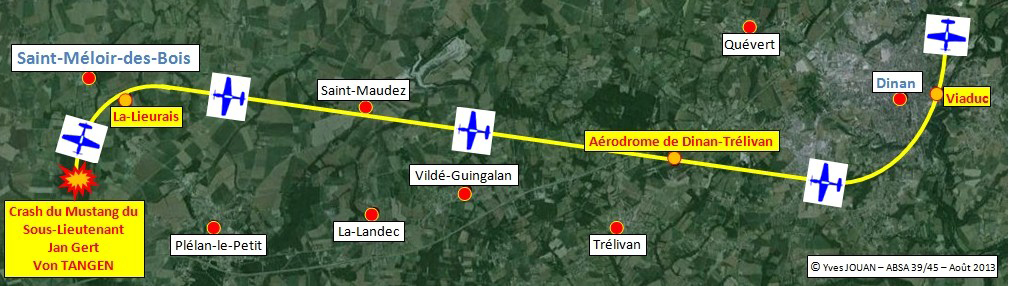

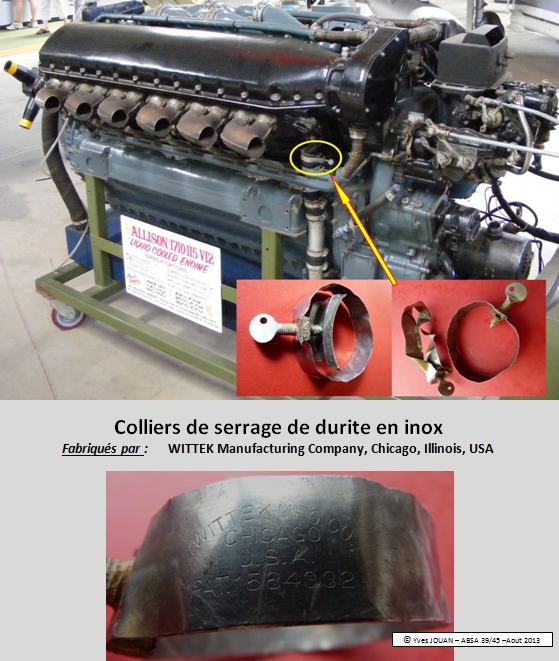

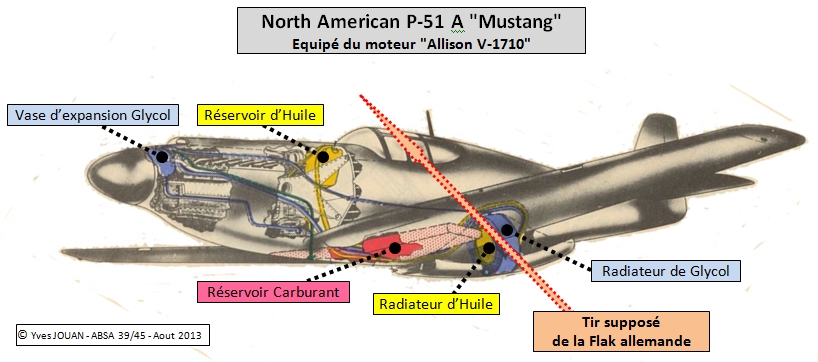

Moreover the plane was equipped with a gun camera coupled with the side guns. Opening fire meant that the camera started working; it was fixed on the extreme end of the left wing. So it was possible to view an attack after a mission. The British had asked for Mustang P-51 Ia to be equipped with four, twenty-millimetre Hispano Suiza guns in each wing, which gave it a very powerful strike force, as did, its 1710-87 Allison engine rating of, 1250 cc’s with 12 V shaped cylinders which gaive it high performance with a 600 km ph maximum speed. When empty the plane weighed 3175 kg in addition to the weight of the fuel (in big tanks), of the ammunition and sometimes of the payload of a 250 kg bomb under the plane (which was not the case during 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen’s mission). On Sunday October 31st 1943 at 3 p.m ( English time), Flying Officer Desmond Alan Cliffton-Mog takes off from Thruxton base in his Mustang Ia registered FD488. His team mate is 2nd Lieutenant Jan Gert von Tangen who is also piloting a Mustang Ia registered as FD554. N coded. They know each other well and have just been on several training missions together. Over British territory which have gone off well. This time they are off on a photographic mission called ‘Poplard’ which consists (while taking photos) of one or two airmen wwatching out in case of an enemy bomb attack and leaving the other to operate safely. Today they have been instructed to photograph the viaducs and bridges between Le Vivier-sur-Mer ( Ille et Vilaine) and Evran ( in the former Côtes d’Armor), both towns being located in the north of Brittany. This photographic mission is meant to bring snapshots of major civil engineering works along the main roads and railways of the area and especially of the Dinan viaduct at the far south of the Rance estuary. Each camera can only take 250 views.

Photographic equipment of a Mustang Mark. Ia

At the beginning of the flight they rendez-vous with two other Mustang Ia from 260 Squadron which are based in Odiham in Hampshire and piloted by Flight Lieutenants Lambert and Smith. They don’t have the same mission; they will fly across the Channel together and split up into two groups and head at high altitude for Roye in the Somme; then, after flying at low altitude they will have to be doubly careful to avoid anti- aircraft gunfire and thus be able to photograph the works along the Paris-Lille railway. The four Mustang fly together. Flight Lieutenant Cliffton-Mog who is the leader has decided on the course and has informed his mates. The four of them are under their superior’s authority, Flying Officer Trevor Eyre Drew Mitchell from 268 Squadron who has given them orders as to their respective missions. They are heading for Portland Bill and its lighthouse set in the southern end of the peninsular. Portland Bill is located south of Weymouth, Dorset in England.

Flying Officer Desmond Alan Clifton-Mogg. (DFC)

The flight goes off in good conditions in favourable weather. The four airmen fly 5 miles (over 7km) over the western coast of Guernsey. They have to avoid anti-aircraft firing defences that have been set in great number by the Germans along the seacoast. They come rapidly in sight of the Breton coast. The group is now heading for the beach of the Verger, north of Cancale ( lle et Vilaine) while gaining altitude to avoid any enemy firing. As expected the group splits up, the airmen communicating by radio and flying towards their respective targets. Lieutenants Cliffton-Mog and von Tangen immediately swoop down to Le Vivier-sur-Mer where they can spot the so-called Angoulême bridge over the river from the Dol marshes to the sea along the coast. They take a photograph and then head for Dol de Bretagne, not staying there long to fly on to Dinan and take several snapshots of the impressive viaduct.

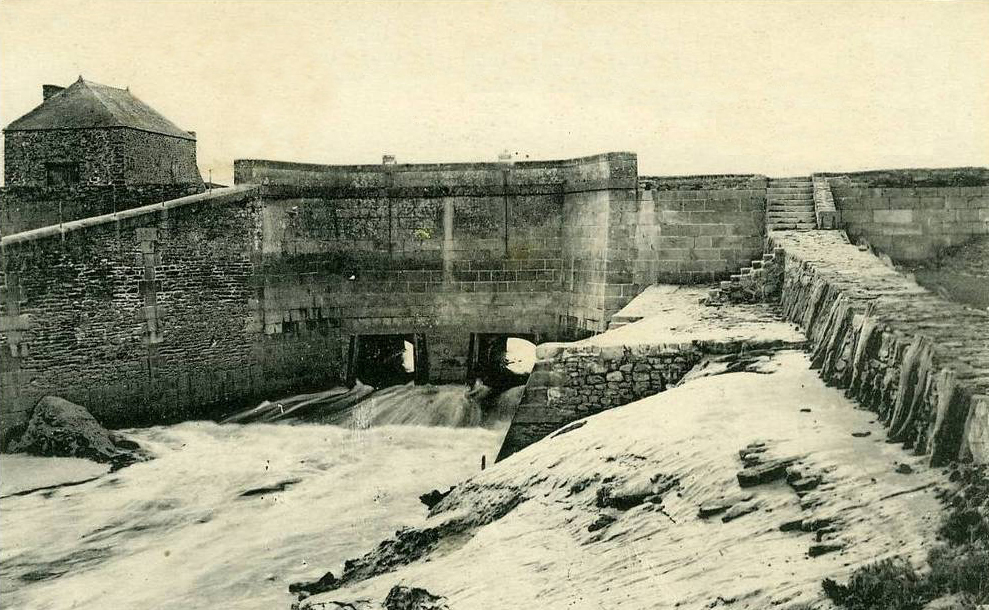

Angoulême Bridge in Vivier-sur-Mer Dinan viaduc

The mission is soon over, the return flight being first westwards and then northwards. One hour and a half earlier they had left England when suddenly tragedy struck. Here is what Lieutenant Cliffton-Mog wrote in his report about his flight back: everything was going off well. Our mission was over. We were flying at average altitude and were 6 miles west of Dol ( he is wrong on this point; he mistook Dol for Dinan given the crash-point) when suddenly my mate’s plane ( 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen’s) banked and swooped on the left, rapidly losing altitude and crashed in a meadow. Everything happened so fast. It was 4.15 pm. I was amazed by such a sudden fall. There were no enemy fighters around us. He didn’t send me any message on the radio. As far as I knew there was no anti air-raid defence point nor any shooting. If there had been any I would have been a target, too. I can’t make out what happened. After flying over the crash-point area I made up my mind to get back straight on heading for the eastern parts of Cap Fréhel and to my base in Thruxton where I landed at 7.20 pm. 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen was reported missing.

Photo of Jan Gert

2nd Lieutenant von Tangen met his death in this accident. He was 26 years old. It was his first mission over enemy territory. He had taken part in several missions training in England, including one on October 22nd 1943 for a test flight with Lieutenant Cliffton-Mog who was testing how much fuel Mustang consumed. They flew over 1000 km together. Three days later on October 25th he was off on a one hour photographic reconnaissance mission at twilight over England. On that day he was with Flight Lieutenants Cormack and Hussey. Madame Odette Buard’s

testimony It seems to me that it all happened on All

Saints’day in 1943 during the afternoon. We

were attending a religious service in Saint

Méloir church when suddenly we heard a crash

and then all was silent. It was wartime. We all

asked ourselves what was wrong. After the service

the news went round. I was told that a plane had

crashed near Ville Rue. We were living in this

village. We hurried back home. Actually the plane

had crashed in Couavra woods nearby. The Germans

were already in the area. My mother had decided

that we should get the cows back by walking along

footpaths to be safer. The following day we heard

that the Germans had captured all the young people

who had been to the place as soon as they arrived

at the crash-point. There was also an adult in the

group. They were taken to Dinan, kept for a few

hours and set free again on the next day. It was

impossible to visit the place because German

sentries were keeping watch. Three days later, late

in the evening Joseph Hervé was told to get

the body of the poor pilot that had been left at

the crash-point, using, his horse and cart. The

dead man was said to be an Englishman. I also

remember that the farmer had taken his torchlight

with him. When the cart arrived in Ville Rue it was

dark. The men heaved the coffin into our house and

laid it on one of our benches. We had not seen the

pilot’s body because it was wrapped with a

cloth. A second coffin had been provided but to no

purpose. The lid was screwed in. The Germans were

attending. At the end one of them suggested they

had a drink before leaving. My mother served them a

snifter. The coffin was brought out and put into a

German car. We never knew where the occupying

forces had buried it. The following days the

Germans discarded the remains of the plane. On the

spot where it had crashed there was a big gap that

was later filled in. Within the context of Weserübung operation that aimed at invading Denmark and Norway, the Germans wanted to have control over the sea trade of Swedish steel that they needed so much. The German army invaded on April 9th 1940 and started to spread out over Norwegian territory. On June 10th Norway was occupied, the country had surrendered, the King and his family had gone into voluntary exiled. In the face of such a tragic situation part of the population who refused occupation was thinking of leaving the country or organizing resistance. Some had already moved to the U.K during the previous months on seeing the turn of events in Europe. They decided to set out at the harbours on the eastern coast of England, which was the only place and also the nearest one that was still free despite Hitler’s blitzkrieg which luckily failed. Numerous seafaring escape networks were set up from Norway. Some had already been in proper use for months. The sea crossings were uncertain because it often took two or three days with the unknown factors due to rough weather in the North Sea. Some escapees met with a tragic end. Many were captured by the German Navy and brought back to Norway. More often than not they were sentenced to death or transported to Germany. Others went down with all hands when their boats were shipwrecked. On March 30 th 1941 a fishing boat named Bovag ( registered M 146G) owned by Mr Vardseth is about to escape at night. It is anchored in Alesund, a harbour town located 230 km north of Bergen. At nightfall 12 men in a small boat boarded the boat very discreetly. They were all longing for escape. Among them was Jan Gert vonTangen who was also resisting the tragedy from which his mother country was suffering. He wanted to play an active part in returning his country to liberty ; that’s why he belonged to the group and was keen to continue the struggle. After a smooth crossing that lasted for 50 hours the boat landed at Lerwick harbor in the Shetland Islands off the coast of Scotland on April 2nd 1941.

The "Bovag" The painter of this picture is Harald BLINHEIM and owner M. Arne VADSETH - ''Norvegian merchant fleet'' 1939 1945

.jpg)

Photo of Jan Gert

The crash of the plane on Sunday October 31st 1943 in Saint-Méloir-des-Bois remains an enigma to the witnesses that have been met so far. The question is still unanswered : “ Why did the Germans arrive on the spot so rapidly while the place was a deserted one?” This event has to be put back in its context. Indeed the Germans were roaming the area on that Sunday. They had arrived early in the morning. A column had been called in from Dinan as reinforcements and was combing through several villages for resistance fighters. The reason for this big operation was that a soldier in charge of mail delivery from Vlassov army had been found dead in a sunken lane near the road from Bourseul to Plancoët on Saturday morning October 30 th 1943. On Sunday 31st October in Bourseul the occupying forces surrounded the village and arrested over 100 inhabitants. About 100 hostages were kept in custody for one day in the village school and were then transferred to Dinan before being set free on the following day at the end of the afternoon. Both events occurred on the same day but one can’t infer that the crash of 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen’s Mustang was ascribed to the presence of the Germans.

The jack plug on Jan Gert’s helmet that was found at the crash-point

Flight Lieutenant Cliffton-Mog’s mission report (he was his team mate) does not mention any possible shooting targeted at them because he had viewed his mate’s crash-point before deciding to fly back to his base. Mr Robert Buard’s testimony casts new light on it all; his father said that on that Sunday in October 1943 he had seen the plane flying at low altitude near Testro village close to Saint Méloir-des-Bois with a trail of smoke. He had thought: ‘that one won’t go a long way’. Monsieur Joseph Jouffe gave us another testimony; he reported that on that Sunday afternoon in 1943 he was looking after his cows in a meadow in Lieuraie village and was having a talk with his aunt Madame Marie Jouffe when suddenly, above their heads they saw a plane that was flying at low altitude heading for the woods of Ville Rue and that they had heard a big muffled sound from the crash of the plane. At the end of the afternoon the Germans arrested 6 young men who had been to the crash-point. (see testimonies in the Appendix). Today from the investigation about the crash of 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen’s plane we would suggest that he was fatally shot as he flew past Dinan-Trélivan airfield.

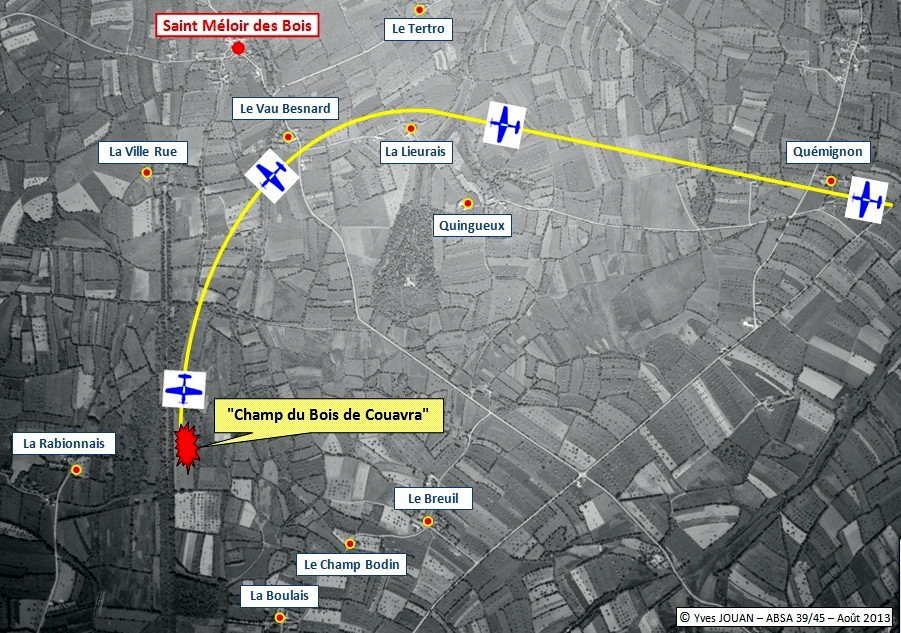

The Mustang before its fall crossed the airspace between the villages of Lieurais and Tertro

Dinan/Trélivan Airfield prewar

Dinan Airfield, between the soldier and in the background, a piece of Flak

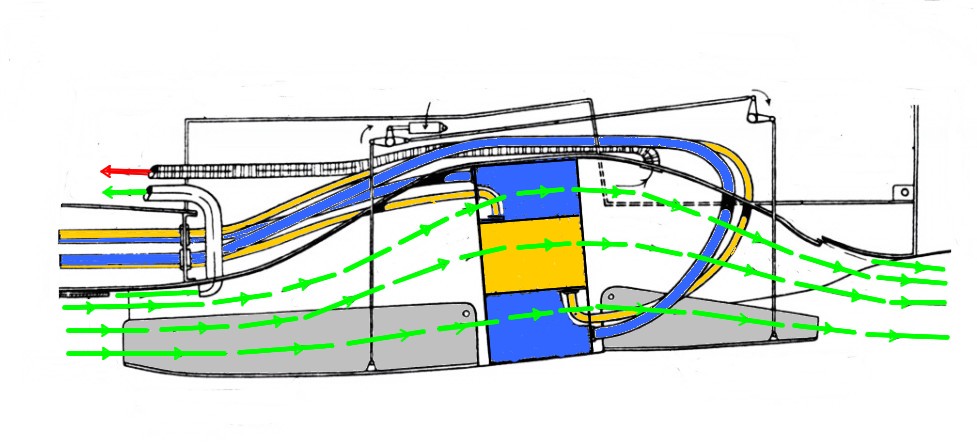

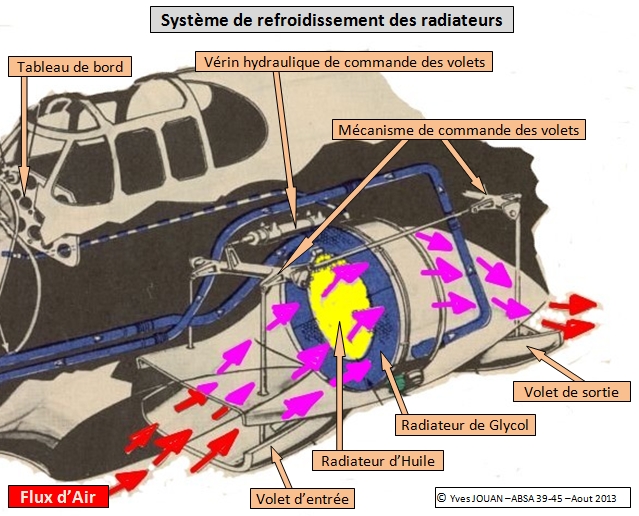

From July 1943 this second rank airfield (registered B28XII- in command in Laval, Mayenne) was occupied by the first and third platoons from Leich Flak Abteilung 912 that operated 6 twenty-mm items called Flak 30 or 38. Its strength involved 63 men together with 77 soldiers from B28/XII Fliegerhorstplatzkommando who had 5 heavy machine guns. If they had heard that planes from the allied forces had been in Dinan area, these gunners would have been rapidly alerted and, ready to shoot. The plane was leaving a trail of smoke behind. It was not smoke but the tank full of glycol (coolant) that had been shell-holed and had started to leak and with the speed of the aircraft would leave a trail behind. This high capacity glycol tank was in the lower part under the engine which made Mustang vulnerable. If the engine had caught fire when the plane crashed, the whole plane would have been set on fire owing to the large quantity of gasoline that was left in the tanks. This was not the case. 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen didn’t send any message. When they were shot at, airmen would tell their mates and would fly at a higher altitude to be able get out of the cockpit and parachute down. Unfortunately this didn’t apply in this case. The plane was in distress flew on for about 10 km. Flight Lieutenant Cliffton-Mog didn’t apply in this that the plane had been hit because he was flying about 1,8 km north of his mate. 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen was buried by the occupying forces on November 3rd 1943 in the British square in Dinard cemetery. They informed the Red Cross International Committee about his death and burial place. In the early days of September 1946 a delegation composed of the Norwegian Royal Air Force and the pilot’s mother went to Dinard to have the body exhumed and transferred to Vestre Gravelund cemetery in Oslo, Norway.

Vestre Cemetery gravlund in Oslo

|

Mr John Corbet Milward for sending photos and biographical information about the family.

Madame Odette Buard, Monsieur Pierre Fleury, Monsieur Albert Olivier, Madame Marie Le Ménager, Monsieur Joseph Jouffe, Monsieur Robert Buard.

Madame Hanne André Danielsen, military attaché. Norway Embassy in Paris.

Yves Jouan, member of ABSA 39-45 for laying out the flight plan in its last minutes.

Madame Véronique Le Sergent Veyrié for translating.

Monsieur David Tye. Researches and detection.

Monsieur Colas who authorized the exploration of the crash-point.

Monsieur Michel Monfort. Photographic touching-up.

Site: Norwegian Merchant Fleet 39-45. Mrs Siri Lawson.

Yannig Kerhousse for providing information about the German unit that occupied Trélivan airfield from July 1943.

Denis Laffont for his book : ‘ L’été des moissons rouges’ who authorized the photo of Trélivan airfield to be published.

Mrs Sarah Dixon and Mrs Linda Jackson for translating the letters from the family.

Document sources: ORB n° 168 Squadron RAF- Personal file of 2nd Lieutenant von Tangen, Ministry of Defence, Air Historical Branch. N° 168 Squadron 1942-1943. Phil H Listemann.

List of the burial places of allied soldiers in Dinard cemetery

Claudine Pigot for his kind permission to publish the sketch made in 1942 by his aunt Madame Yvonne Jean-Haffen on Kommandantur Dinan located at 29 rue de Brest. Thank you to Mrs. Florence Rene Service museums of Dinan.

.jpg)